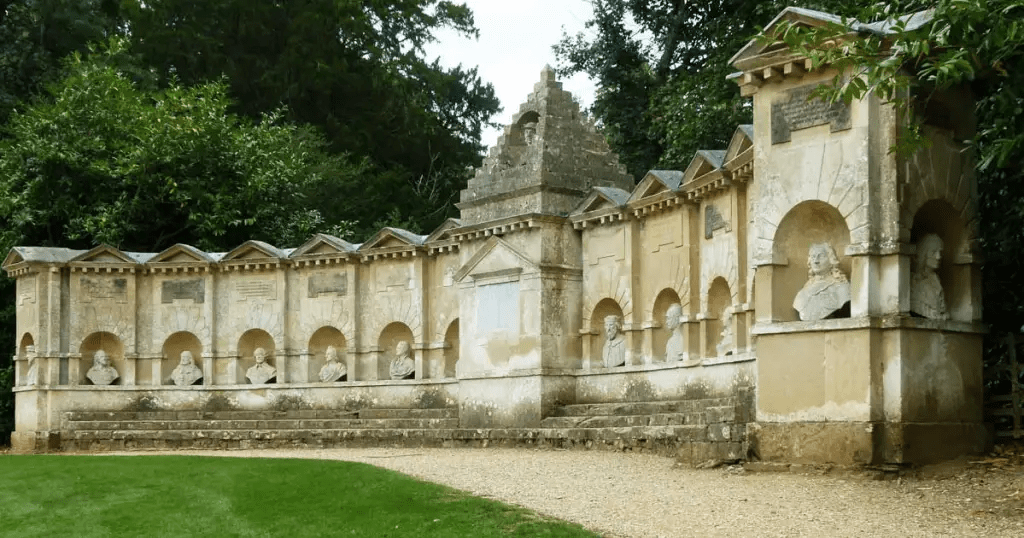

As promised another post for the blog this summer – and further soon to come. This one broaches the subject of the Classics curriculum in my school in Buckinghamshire, where we offer Greek and Latin through GCSE and at A level. The school itself could not be a more natural (and stunning) environment for these subjects, grounded as it is amidst the most splendid classically inspired architecture, where the beauty and personality of ancient culture comes fascinatingly to life in all sorts of ways. Some pictures to illustrate below…

Nonetheless, numbers doing the subject in the school are not at an all time high, since we can no longer rely on the privilege – long ago lost – of being a compulsory subject. Now, Greek and Latin exist very much as an optional choice in the school curriculum, and this is the case from pupils’ first point of entry into the school at age 13. Gone, then, are the days, when a Richard Branson – one of the famous ex-pupils to attend the school – would face compulsory lessons in Greek and Latin as part of his curriculum. More on the changing face of schoolroom Classics and its place in the curriculum another time, no doubt.

My point in the present post is simply that a big aim of mine over the next year is going to be to inject life (and pupil numbers) into Classics at the school. To do this, I plan to tackle the issue of the year 9 curriculum: the first term of year 9 is the point where pupils choose whether they will continue with a classical subject up to GCSE. They need to have a great experience in that term, and to see that the subject(s) are for them. At present numbers are pretty low for Latin, but particularly so for Greek (only 2 or 3 per year). How, though, to fix this?

Well, two ideas. First, any plan to do so must reckon with the fact that pupils enter the school in year 9 with quite varied experiences of the language(s) from their previous schools. Some enter as complete beginners. Some enter having studied Latin (at least) for 3 or so years. So my plan is to create a two-tier experience for the pupils in the subject over my first year with them: for tier 1 pupils, offer a full introduction and grounding in the basics (tier 1 would include not just beginners but pupils who have studied the subject before); for tier 2 pupils, a compendium of additional translations and language work.

And this is where my second idea, which itself has two prongs, comes in: a) introducing them to Greek history/culture through Latin stories – and indeed b) to Greek language itself.

On a): the idea here is to use Latin as a basis to explore Greek stories and myths. Well, not exclusively Greek. What I really want to offer is a survey of some of the most interesting and absorbing short stories in Greek literature – from Herodotus to Thucydides to Xenophon to Homer and other poets. So there will be a booklet of stories which will allow just this. Pupils will build up a sense of how Greek writers tell fascinating stories – and would be even more fascinating to read in their own original language than in Latin. But starting by reading Greek stories in Latin is not a bad way to go. On b): pupils will have access to a basic Greek language booklet, which they can work through if they finish Latin tasks early in class.

On the basis of these experiences, I hope some will opt to take up Greek GCSE, in addition to Latin. We will see how it goes. The beauty of teaching Classics is that the material never fails to come alive: I am very much looking forward to reading lots of fun Greek stories (in Latin, at least initially) with my new pupils next term.