Below is the text of an article I recently wrote for our school languages magazine. Much of the factual content of the article is based on reading I did in the OCD (Oxford Classical Dictionary), and it may be that certain sentences feature a misunderstanding or two, since I am no expert philologist. Nonetheless I thought readers of this blog might enjoy reading it.

Greek and Latin are today the best-known languages of ancient Europe – and there are good reasons for this. First, the speakers of these two languages produced literature and inscriptions which survive to us in large quantities far exceeding what we possess from most other ancient linguistic traditions; second, both languages were widely used, not just in a narrow geographical zone, but throughout the ancient Mediterranean, over many centuries; and third – both languages have enjoyed an amazing afterlife. They form a big part of the basis of the most commonly-spoken European languages today (English, French, Italian, Romanian, Spanish etc). And, equally crucially, the culture and literature of the original speakers of Latin and Greek have exercised a dramatic and influential impact on subsequent literary and cultural history.

The prominence of Latin and Greek is a reminder of how language connects with power. It was early Greek colonisation, and the later empire of Alexander the Great, which successfully spread the ancient Greek language across the ancient Mediterranean and beyond. And it was Roman military conquest which resulted in the spread of the Latin language – first, as Rome conquered Italy, throughout the Italian peninsula; later, as Rome expanded her borders, throughout the ancient Mediterranean, into France, Spain, North Africa, and beyond – even to that far corner of the empire, Britain. Latin and Greek, then, are languages of empire, not just literature and culture – and their ancient (and modern) prominence reflects this.

In spite of this background, I often pause to wonder, as a teacher of Classics, about the other languages of the ancient world – the ones we know less about; the ones we hardly know at all; the ones of which no trace whatsoever survives. In particular, since much of my day is consumed with the Romans and their Latin language, I find myself wondering about the other languages of ancient Italy.

As the Romans spread from their home city of Rome to complete their conquest of Italy in the late centuries BC, they inevitably brought their own language (Latin) along with them into the areas they conquered. It is clear enough that Latin became quickly established throughout Italy as a language of politics, diplomacy and trade. But what happened then to the languages of the conquered peoples? One broadbrush comment we can make here is that these other languages continued to be used. They did not just vanish once Latin appeared on the scene. But what broad features of the languages and their use can we identify beyond this?

To start off with, we must register that we can say almost nothing at all about many of the languages in question. Of Paelignian, Marrucinian, Volscian, Marsian and Aequian, for example, all languages of ancient Italy, we know almost nothing beyond the fact that they existed and were spoken. About other languages we can say more than this. Take the closely related languages of Oscan and Umbrian, both of which were spoken in southern Italy.

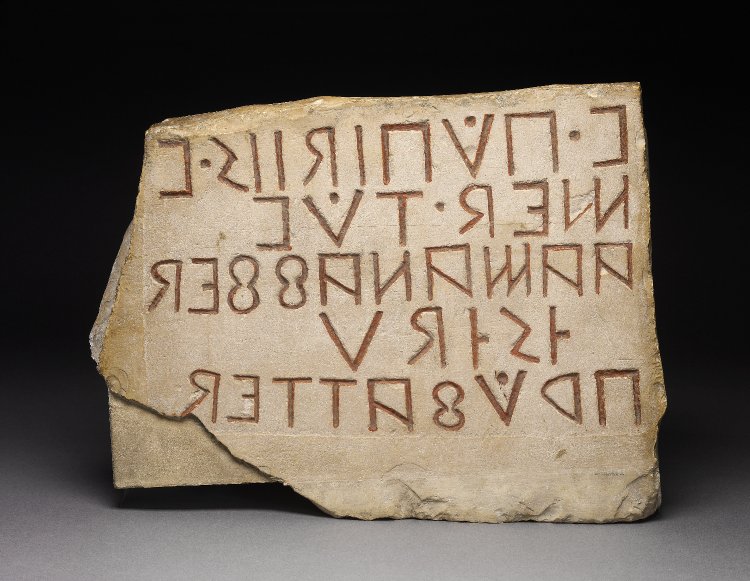

Umbrian is known chiefly from a collection of bronze tablets which survive from the 2nd century BC and from a collection of short inscriptions from c. 400 BC. As with Umbrian, our best evidence for Oscan comes from an early period (pre-Roman conquest). Oscan was clearly widely spoken in South Italy. It was the language of the Samnites, the tribe who took over the region of Campania in the 5th century BC. The Romans called speakers of Oscan ‘Sabelli’. The Oscan alphabet is known to us: there are coin legends, building inscriptions, texts painted on walls at Pompeii, curses, funerary inscriptions and more. Users of Oscan were not afraid to use the language flexibly: we have evidence of its being transcribed into the Greek, and later the Latin, alphabets, for example. In terms of their linguistic relationship, Oscan and Umbrian have a close relationship to one another, moreover.

Another important language of ancient Italy was Greek. Greek colonies were established very early in ancient Italy and down into Sicily – and the Greek language found a home in these settlements. The geographical zone in which Greek was used has been known as ‘Magna Graecia’ (‘Great Greece’!). One impact of the use of Greek in this area is the drift of Greek loanwords into other Italian languages – including Latin. Greek continued to be an important language in Italy after the Romans conquered the peninsula. For example, when St Paul addressed a community of Christians in Rome itself in the first century AD in a text which came to form part of the New Testament, he wrote to them in Greek. And Greek remained an important language for Christianity at Rome.

Fleeting glimpses of other noteworthy ancient languages appear in our evidence. A form of the Celtic language known as Lepontic was also used in ancient Italy, for instance: inscriptions found in North West Italy give evidence of its presence. Meanwhile, down in Sicily, we have evidence of the use of the important North African language Punic.

The Etruscans, and their Etruscan language, represent a major topic in their own right. Our historical record is patchy but it seems the Etruscans flourished especially as a major power across Italy in the 8th and 7th centuries BC. Inevitably their political strength is reflected in the spread of their language. The Etruscan language is interesting especially because it seems to have almost no obvious linguistic relationship to other languages we know about. This has made it particularly challenging for historians to decode the 9000 or so surviving Etruscan inscriptions, most of which are found in Etruria in central Italy.

There is something haunting about considering the use of these ancient languages. Once at the heartbeat of their respective towns, cities and societies, they are now known to us only dimly through small scattered evidence. Yet their traces remind us of the remorseless sweep of history, and of the fact that, in time, even the languages of great powers – such as Etruria, or Rome herself, or – dare we say it? – of the great powers of 21st century modernity – disappear or develop into something new.

Further Reading: The Oxford Classical Dictionary – articles on ‘Languages of Italy’, ‘Oscan’, ‘Sabellian’, ‘Etruscan Language’.