The time is fast approaching when my third form (year 9) pupils will have to make their options choices for GCSE. Since Latin is no longer front and centre of the school curriculum in the school at which I work (as it was once upon a time), this means Latin will be up on the market as one among several options the pupils will decide between. And, for me, this means it will be a case of making a pitch for Latin, as a subject, which will enable it to compete with such alternatives as Art, Computer Science, Geography, History, Music, Spanish and plenty more besides.

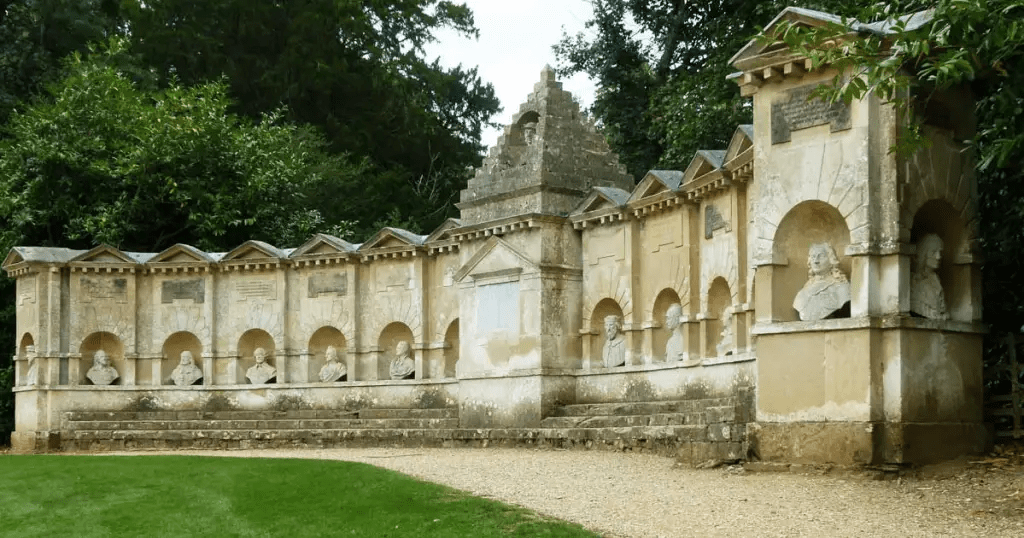

In past years, my pitch for the subject has tended to focus on its broad-ranging fascination – at GCSE you get to study not just language and words, but interesting stories, and plenty of Roman literature and culture. I emphasise that pupils seldom regret choosing Latin; that it is particularly suitable for the academically capable and ambitious; that it allows you to gain access to another world far-removed from our own (yet eerily familiar) in a way few other subjects will. It is, in short, a subject for life, not just the classroom. This has usually gone down well, even if it doesn’t necessarily convince some among the hardline utilitarian or ‘relevance-obsessed’ 13 year olds I sometimes come across. At my current school, with its backdrop of neoclassical architecture and its stunning gardens, replete with classically-themed temples, grottos and sculptures, the ‘relevance’ of the Classics hardly features as a topic for debate, since its presence all around us makes it an obvious source of fascination.

In fact, I have made a point of taking all 40 or so third formers on short walks out to Dido’s Cave and the Temple of Venus (at the edge of the gardens). I have done this partly to ensure that the school’s topography and architecture is very much on their minds as they make their options choices, and partly to dovetail with their initial explorations of the story of Virgil’s Aeneid, in which both Venus and Dido feature prominently.

But the ‘new’ Latin pitch I refer to in this blogpost’s title refers not to these walks, but to a bolder line of approach I have started to adopt in advertising the merits of the classical subjects (not just Latin but Greek also) to students. This pitch aims to address the underlying utilitarian concerns pupils bring into play when weighing up classical study.

It runs something like this: every day of your lives, in whatever line of work you end up going into, and in the context of whatever relationships you go on to form, you are going to be reliant, most likely, on the English language, its use and manipulation, and on your powers of expression. Don’t underestimate the importance of this. Your use of this language will establish the contours of your most valued relationships – with colleagues, friends, family members, and in affairs of the heart. Skill with language – and the ability to see through others’ words – will also allow you to escape the thoughts and linguistic tricks of others when they are being cruel or manipulative. Being able to use language skilfully will be vital, both for enjoyment and success.

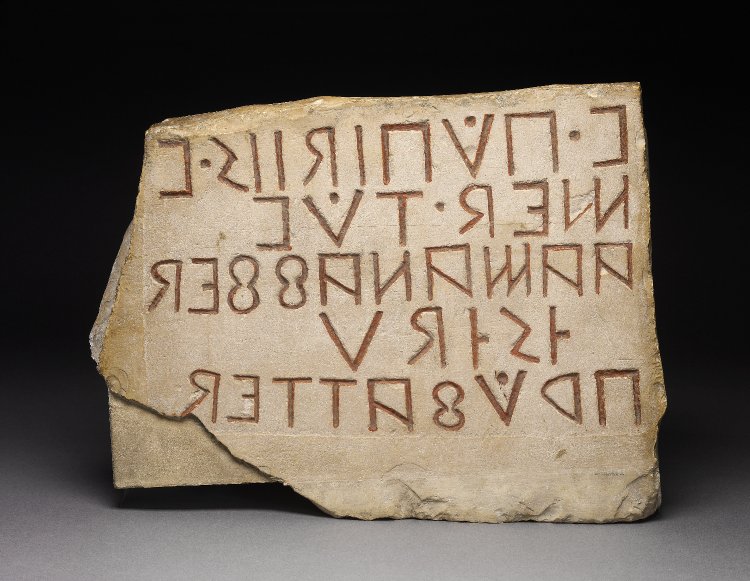

What could give you a better grounding in your use of language than a thorough grounding in Greek and Latin? You may think that these languages are incidental to modern life, but the lie of that will become apparent if you just look closely at the words of that very phrase. The fact is that you are already speaking and thinking in Latin and Greek, much of the time, whether you know it or not. Wouldn’t it be ‘useful’ to get to know better this central feature of your ‘toolkit’ for life? To see what’s really going on in your use of words? To enjoy getting to know better how many of these words were used – in their original form – by their most skilled ancient users?

Perhaps this all sounds a tad melodramatic or intense. I had not been in the habit of pitching about the attractions of Latin in this way before the past few months. But as time passes, and as the newspapers carry more and more stories about the gradual and horrifying dawn of a post-literate society, it seems right to turn the focus of any pitch for Classics onto the centrality of words in our lives, their power to enrich us, their charm and magic.

Postmodernity has tended to frown on ‘logocentricity’ (one of its uglier jargonistic neologisms meaning a fixation on the written word as a means of conveying truth) while developing a desperately ugly and unapproachable form of academese. While I take the point that the written word is not, and could never be, the sole measure of truth and meaning, the flight from great writing, and from the ennobling use of language more generally, over recent decades is one Classics teachers are particularly well-placed to start speaking up against.